The art of preserving fruits through sugaring has been practiced for centuries, a delicate dance between science and tradition. At its core lies the fascinating principle of osmotic equilibrium, where nature seeks balance even in the sweetest of preparations. This invisible force governs the transformation of fresh fruit into glistening candied delights, creating a symphony of flavors and textures that have graced royal tables and humble kitchens alike.

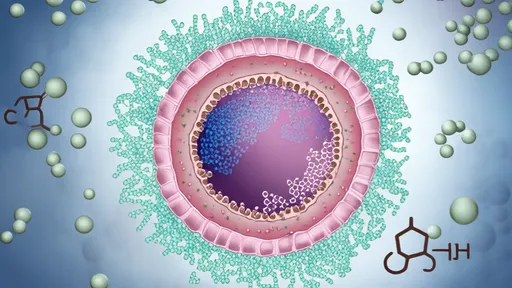

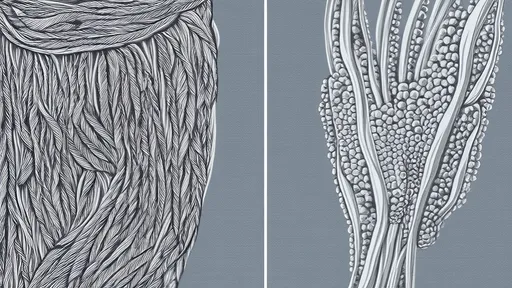

When fresh fruit meets concentrated sugar syrup, an intricate molecular ballet begins. The high sugar concentration outside the fruit cells creates what scientists call a hypertonic environment. Water molecules within the fruit's cellular structure, ever obedient to the laws of thermodynamics, begin migrating outward toward the syrup. This exodus continues until equilibrium is reached—when the sugar concentration inside and outside the cells balances. The process doesn't stop there; sugar molecules gradually infiltrate the fruit's cellular matrix, replacing lost water and creating that characteristic candied texture.

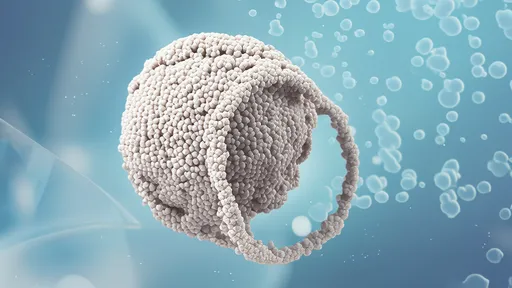

The concentration gradient—the difference in sugar concentration between the fruit and its surrounding syrup—acts as the driving force behind this transformation. Artisans have learned through generations of practice that controlling this gradient is crucial. Too steep a gradient can cause the fruit to shrivel excessively as water rushes out too quickly. Too gentle a gradient prolongs the process unnecessarily. The most skilled confectioners employ a stepwise increasing concentration method, gradually raising the syrup's sugar content over days or weeks to achieve perfect penetration without compromising texture.

Temperature plays a subtle yet significant role in this osmotic drama. Warmer environments accelerate molecular movement, causing faster water migration and sugar absorption. However, excessive heat can break down cell walls, turning prized fruit into mushy disappointment. Traditional methods often rely on room temperature processes that may take weeks but yield superior results. Modern commercial producers sometimes use controlled heat to speed production, though purists argue this sacrifices quality for efficiency.

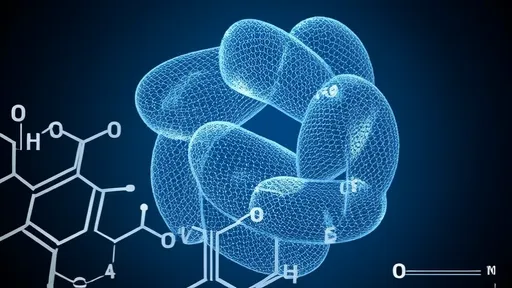

The choice of sugar affects both the process and final product. While sucrose (common table sugar) dominates traditional recipes, some artisans experiment with glucose, fructose, or honey. Each sweetener interacts differently with fruit tissues due to variations in molecular size and structure. Honey, for instance, contains larger molecules that penetrate more slowly than sucrose, resulting in distinct textures and flavor profiles. The type of sugar also influences the syrup's viscosity, which in turn affects how easily it can permeate fruit tissues.

Fruit characteristics dramatically impact the sugaring process. Dense fruits like citrus peel or pineapple require longer processing than porous strawberries or peaches. The fruit's natural sugar content creates its own osmotic pressure—high-sugar fruits like figs experience less dramatic water loss than tart cherries or green plums. Some fruits develop protective wax coatings that must be carefully removed or pierced to allow proper syrup penetration. These variations explain why experienced confectioners treat each fruit type as a unique challenge requiring customized approaches.

Beyond texture, the osmotic process profoundly influences flavor development. As water departs, it concentrates the fruit's natural flavors while making room for sugar molecules. This dual action creates the intense yet balanced taste profile characteristic of quality candied fruits. The gradual nature of traditional methods allows complex flavor compounds to develop and mature, much like aging fine wine. Some connoisseurs can identify processing methods by taste alone, distinguishing between rushed commercial products and patiently crafted artisanal specimens.

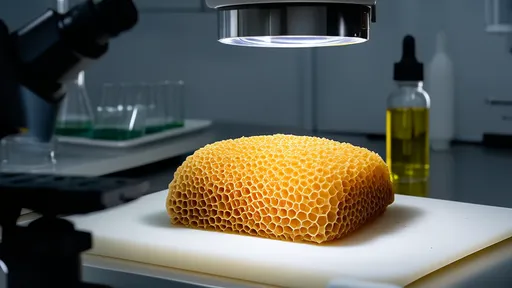

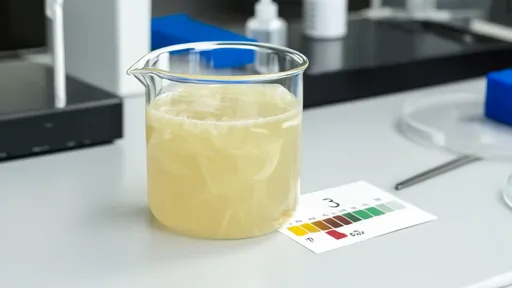

Modern food science has quantified what traditional practitioners knew intuitively. Studies using refractometers show how sugar content changes in both fruit and syrup throughout the process. Microscopic examination reveals how cell structures alter during sugaring. These scientific insights help troubleshoot common problems like case hardening—when fruit forms a sugar-crusted barrier that prevents proper penetration. Understanding osmotic principles allows producers to adjust variables like syrup concentration, temperature, and processing time for consistent results.

The cultural significance of candied fruits reflects their technical sophistication. In medieval Europe, they symbolized wealth and status—only the affluent could afford such labor-intensive luxuries. Today, they remain holiday staples across cultures, from Italian panettone to Chinese mooncakes. The osmotic process that preserves them also preserves culinary heritage, allowing generations to experience flavors essentially unchanged for centuries. Artisans who master these techniques become keepers of living history, their hands continuing practices refined over millennia.

Health considerations have brought new attention to osmotic principles. While traditional recipes rely on high sugar concentrations for preservation, modern variations explore reduced-sugar alternatives. Some innovators use osmotic dehydration with alternative sweeteners or even savory brines, applying ancient techniques to contemporary dietary preferences. Understanding concentration gradients helps create products that balance safety, texture, and flavor while meeting evolving consumer demands.

From scientific laboratories to home kitchens, the osmotic magic behind candied fruits continues to captivate. It represents one of humanity's earliest applications of food science—a marriage of observation and intuition that predates modern chemistry by centuries. Each glistening piece of candied fruit embodies nature's relentless pursuit of equilibrium, harnessed by human ingenuity to create something greater than the sum of its parts. As long as people cherish both sweetness and tradition, this delicious demonstration of osmotic principles will endure.

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025