The art of fermenting vegetables into tangy, probiotic-rich pickles has been practiced for millennia across cultures, yet the delicate dance of microbial activity beneath the brine remains a subject of fascination for both home fermenters and food scientists. At the heart of this transformation lies a critical metric: pH. The logarithmic scale measuring acidity or alkalinity becomes the silent conductor orchestrating microbial succession, enzyme activity, and ultimately, the safety and flavor profile of fermented pickles.

When fresh vegetables are submerged in brine, they carry with them an ecosystem of microorganisms clinging to their surfaces. The initial pH of this environment typically hovers between 5.5 to 6.5 – slightly acidic but still hospitable to a wide range of microbes. This neutral beginning belies the dramatic biochemical drama about to unfold as competing bacterial communities wage invisible warfare through acid production.

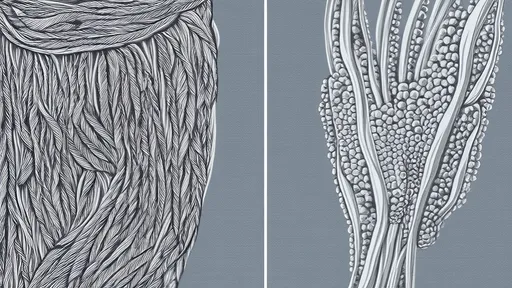

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB), the undisputed champions of vegetable fermentation, begin their ascent as oxygen depletes in the anaerobic brine environment. These hardy microorganisms – including species like Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Lactobacillus plantarum, and Pediococcus cerevisiae – possess the unique ability to convert sugars into lactic acid through glycolysis. As they metabolize, the pH begins its steady downward trajectory, creating an environment increasingly hostile to spoilage organisms while favoring acid-tolerant LAB strains.

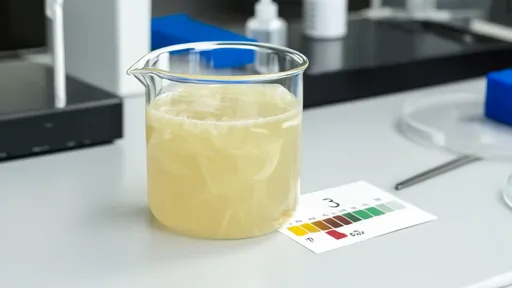

The pH drop follows a characteristic sigmoid curve during successful fermentation. An initial lag phase shows minimal pH change as LAB populations establish themselves. This gives way to a rapid decline phase where pH may plummet from 6.0 to 4.0 within 48-72 hours as exponential bacterial growth occurs. Finally, the curve flattens during the stationary phase as sugar substrates become depleted and metabolic activity slows, typically stabilizing between pH 3.2-3.8 for fully fermented pickles.

This acidification serves multiple crucial functions. Below pH 4.6, the growth of pathogenic bacteria like Clostridium botulinum becomes inhibited, rendering the product shelf-stable without refrigeration. The acidic environment also promotes pectin breakdown, yielding that characteristic pickle crunch while preventing vegetable mushiness. Perhaps most importantly for culinary applications, the decreasing pH creates the bright, tangy flavor profile that defines quality fermented pickles.

Monitoring pH evolution reveals fascinating microbial dynamics. Early-stage fermentations (pH >4.5) often show heterofermentative LAB like Leuconostoc species dominating, producing a mix of lactic acid, acetic acid, ethanol, and carbon dioxide. As acidity increases, homofermentative species like Lactobacillus plantarum take over, efficiently converting sugars purely to lactic acid. This succession explains why early fermentation may taste subtly different from mature pickles – the microbial cast changes along with the pH.

External factors dramatically influence the pH progression. Brine concentration acts as a selective pressure – lower salt levels (2-3%) encourage faster acidification but risk yeast overgrowth, while stronger brines (5-10%) slow pH drop but favor LAB dominance. Temperature plays a similar balancing act, with warmer environments (18-22°C) accelerating fermentation but potentially encouraging off-flavors, while cooler temperatures (10-15°C) yield slower, more controlled acid development.

The vegetable substrate itself contributes to pH dynamics. Cabbage naturally contains more fermentable sugars than cucumbers, often resulting in quicker pH drops for sauerkraut versus pickles. Addition of calcium chloride maintains crispness but can buffer against rapid acidification. Even the vegetable's physical preparation matters – shredded surfaces expose more sugars for microbial access compared to whole vegetables, affecting the pH descent rate.

Modern fermentation science has revealed intriguing nuances in pH management. Some producers now employ back-slopping – adding brine from previous successful batches – to inoculate new ferments with an established LAB community, ensuring rapid pH decline. Others experiment with controlled acidification by food-grade acid additions at the start, creating an immediate selective environment for LAB while suppressing competitors.

Troubleshooting pH-related fermentation issues requires understanding these complex interactions. A sluggish pH drop may indicate insufficient LAB populations, excessive oxygen exposure, or inadequate fermentable sugars. Conversely, an overly rapid pH crash can produce harsh, unbalanced flavors as certain metabolic pathways become dominant. Experienced fermenters learn to "read" the pH curve much like a baker monitors dough rise – as a living process requiring careful observation.

Advanced techniques like pH-stat fermentation allow precise control in commercial operations, automatically adjusting conditions to maintain optimal acidification rates. Meanwhile, home fermenters have embraced simple pH test strips as valuable tools for monitoring progress. This democratization of pH measurement has empowered a new generation of pickle enthusiasts to move beyond guesswork in their craft.

The relationship between pH and pickle quality extends beyond fermentation. Finished product pH determines whether pasteurization becomes necessary (for higher pH products) and influences flavor perception during consumption. Interestingly, small pH differences (3.4 vs 3.6) can markedly affect taste balance and microbial stability, explaining why commercial producers carefully standardize this parameter.

Emerging research continues to uncover pH-related fermentation insights. Studies on bacteriocin-producing LAB strains reveal how certain bacteria create additional antimicrobial compounds most effectively at specific pH ranges. Investigations into pickle microbiome resilience show how acid-adapted communities can protect against pH fluctuations during storage. Even the much-hyped probiotic benefits of fermented vegetables appear pH-dependent, with certain beneficial strains surviving digestive transit better when originating from low-pH environments.

As fermentation regains its place as both preservation method and culinary art form, understanding pH's central role becomes ever more valuable. From guiding traditional recipes to informing high-tech production methods, the humble pH scale remains indispensable for creating safe, delicious fermented pickles. Whether observed through laboratory instruments or deduced from the familiar tang of a perfect sour pickle, this invisible acidification process continues to connect modern eaters with one of humanity's oldest food transformations.

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025