The texture of cooked rice, particularly its stickiness, is a defining characteristic that influences culinary preferences across cultures. While numerous factors contribute to rice quality, the amylose content of rice starch emerges as the single most critical determinant of this textural property. This invisible component within each grain holds the key to understanding why some rice varieties cling together while others remain separate and fluffy.

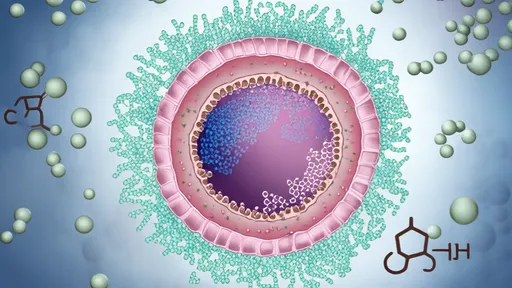

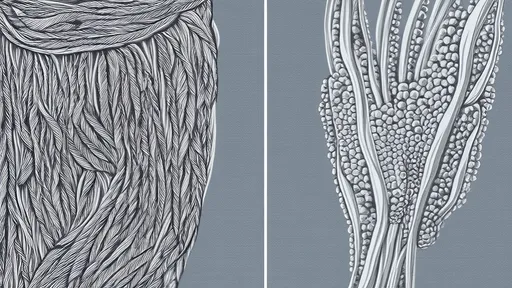

Amylose, a linear polymer of glucose molecules, constitutes one of the two main components of starch in rice endosperm. Unlike its highly branched counterpart amylopectin, amylose molecules tend to form more ordered structures during cooking and cooling. Rice varieties containing 20-30% amylose typically produce fluffy, separate grains ideal for pilafs or biryanis, while those with less than 20% yield the sticky rice preferred in many Asian cuisines. The precise amylose measurement has become so crucial that modern rice breeding programs use it as a primary selection criterion when developing new varieties.

The relationship between amylose content and stickiness follows a clear inverse correlation. During the cooking process, amylose molecules leach out from the starch granules and form networks between grains as the rice cools. Higher amylose concentrations create stronger intermolecular bonds that prevent grains from adhering, while lower levels allow the sticky amylopectin to dominate the texture. This explains why Japanese short-grain rice (typically 15-20% amylose) becomes perfectly sticky for sushi, while Basmati (22-28% amylose) maintains its distinctive separateness.

Climate conditions during rice growth significantly impact final amylose levels. Research demonstrates that higher temperatures during grain filling tend to decrease amylose content, resulting in stickier rice from the same variety. This environmental sensitivity poses challenges for consistent quality but also offers opportunities for growers to target specific markets by adjusting planting schedules. The phenomenon helps explain why the same rice variety may exhibit slightly different cooking properties across growing regions or seasons.

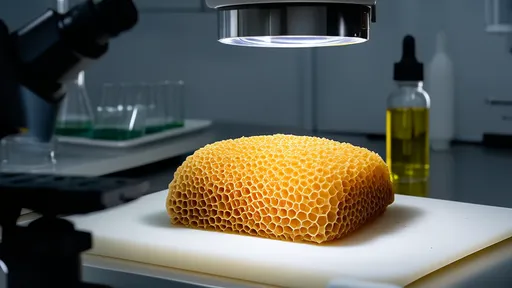

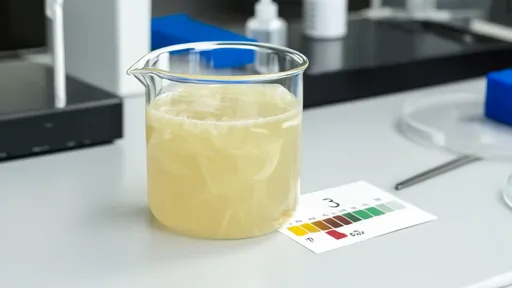

Traditional rice classification systems have long recognized these textural differences without understanding their biochemical basis. The terms "indica," "japonica," and "javanica" historically described rice types with distinct cooking qualities that we now know correspond to typical amylose ranges. Modern laboratory techniques like iodine binding assays and high-performance liquid chromatography have replaced subjective assessments, allowing precise amylose measurement down to 0.1% accuracy.

Consumer preferences for rice texture vary dramatically by region, creating distinct market segments. Southeast Asian markets predominantly demand low-amylose sticky rice for easy eating with chopsticks, while Indian and Pakistani consumers prefer high-amylose varieties that remain separate when mixed with curries. This cultural dimension adds economic significance to amylose content, with price premiums often attached to varieties that hit the ideal amylose target for specific culinary applications.

Rice processing methods can influence the apparent stickiness regardless of inherent amylose content. Parboiling, a hydrothermal treatment common in South Asia, gelatinizes the starch before milling and can make even high-amylose rice stickier than its native state would suggest. Similarly, different cooking techniques - water ratios, soaking times, pressure cooking - can somewhat modify the final texture, though they cannot fundamentally overcome the limitations set by the grain's natural amylose percentage.

Emerging research suggests amylose content affects more than just texture. Digestibility studies indicate that higher amylose rice tends to have a lower glycemic index, making it potentially more suitable for diabetic diets. The slower digestion rate occurs because amylose's linear structure forms more resistant starch than the highly branched amylopectin. This nutritional dimension adds another layer of complexity to breeding programs aiming to optimize multiple quality parameters simultaneously.

Modern genetic techniques have identified several genes controlling amylose synthesis, with the Waxy (Wx) gene being particularly influential. Different alleles of this gene produce varying amounts of granule-bound starch synthase, the enzyme responsible for amylose production. Breeders now use molecular markers for these genes to accelerate development of new varieties with precisely calibrated stickiness characteristics, reducing the need for extensive field testing of cooking quality.

The global rice trade has developed sophisticated testing protocols to ensure amylose specifications are met for different market segments. Export contracts frequently specify amylose ranges, and disputes occasionally arise when shipments fail laboratory analysis. This commercial reality underscores how a single biochemical parameter has become central to an international commodity market worth billions annually.

Looking ahead, climate change may disrupt traditional amylose patterns in rice-growing regions. As temperatures rise, historical growing areas may find their rice becoming stickier than desired, potentially requiring shifts in varietal selection or cultivation practices. Simultaneously, breeding heat-tolerant varieties that maintain consistent amylose levels under stress represents an active area of agricultural research with significant economic implications.

For home cooks puzzled by inconsistent rice textures, understanding amylose content provides practical guidance. Checking packaging for amylose percentages or rice type descriptions can help select the right variety for specific dishes. When unavailable, a simple water test - where high-amylose rice tends to sink while low-amylose varieties float - offers a rough indicator of likely cooking behavior.

The science of rice texture continues to evolve, with researchers investigating how amylose interacts with other components like proteins and lipids to influence final product quality. What remains unchanged is the central role of this unassuming starch molecule in determining one of humanity's most fundamental food experiences - the perfect bowl of rice, tailored to cultural tradition and personal preference alike.

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025