The relationship between soybeans and rhizobia represents one of nature's most fascinating symbiotic partnerships. Across countless fields worldwide, this invisible collaboration quietly fuels agricultural productivity while reducing dependence on synthetic fertilizers. Farmers and scientists alike have long marveled at how these two organisms communicate through sophisticated biochemical signals to establish their nitrogen-fixing cooperation.

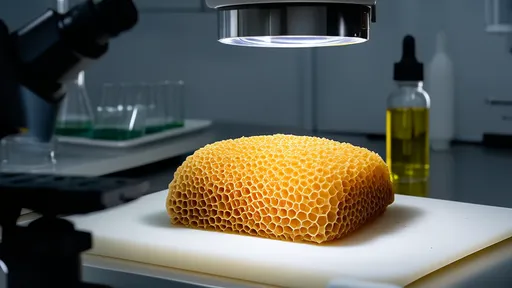

Walking through a soybean field during peak growing season reveals subtle clues about this underground partnership. Healthy nodules appear as small pinkish bumps along the root system - their color indicating active nitrogen fixation. The most effective nodules typically cluster on the upper taproot rather than lateral roots, a detail experienced agronomists use to assess symbiotic efficiency. These living nitrogen factories contain leghemoglobin, a plant-produced protein that creates the oxygen-free environment rhizobia require to convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia.

Seasonal patterns dramatically influence nodulation dynamics. Early-season observations often show sparse nodule formation as the partnership establishes itself. By mid-season, a thriving soybean plant may host hundreds of nodules working in shifts - older nodules senescing while new ones form. The most productive fields demonstrate what researchers call "synchronized senescence," where nodules naturally degrade as pods fill, efficiently recycling nutrients back into the plant.

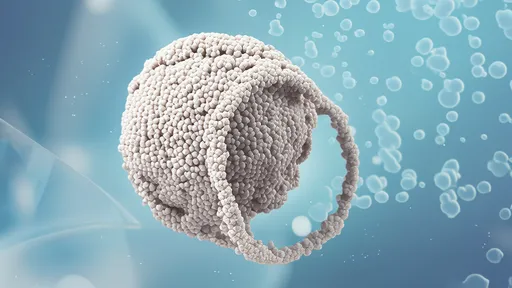

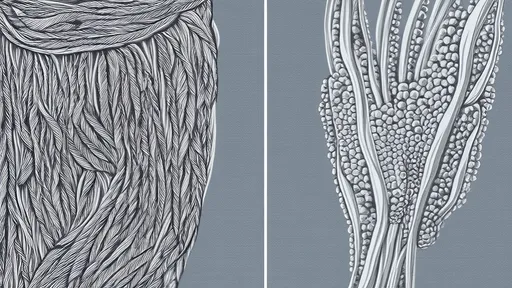

Microscopic examination reveals the intricate infection process where rhizobia enter root hairs through infection threads. The plant's cortical cells then divide rapidly to form the nodule structure. What makes this relationship extraordinary is its specificity - particular rhizobium strains match with specific soybean varieties through an elaborate molecular handshake. Field technicians often carry strain identification kits to verify whether applied inoculants have successfully established.

Environmental factors constantly reshape this delicate biological negotiation. Soil temperatures below 60°F or above 90°F can severely limit nodule formation. Compacted soils create physical barriers to root exploration and rhizobia movement. Salinity stress triggers early nodule senescence, while phosphorus deficiency starves the energy-intensive nitrogen fixation process. Observant farmers notice these interactions through stunted growth patterns and pale green foliage indicating nitrogen starvation.

The practical implications of these field observations are profound. Rotation practices significantly impact nodulation efficiency, with continuous soybean plantings often showing reduced symbiotic performance. Many progressive farmers now use green manures or cover crops to maintain diverse soil microbiomes that support effective rhizobium populations. Equipment operators have learned to adjust tillage practices to protect the crucial topsoil layer where most rhizobia reside.

Modern precision agriculture tools provide new ways to monitor this symbiosis at scale. Multispectral imaging detects subtle changes in leaf color that indicate nitrogen fixation rates. Soil sensors track the oxygen gradients around root zones that influence nodule activity. Some innovative operations have begun mapping nodulation patterns across fields, creating prescription maps for variable-rate inoculant applications in subsequent seasons.

This ancient partnership continues to reveal its complexity through field observations. The soybean plant carefully regulates nodule numbers based on its nitrogen needs, producing inhibitory compounds when sufficient nitrogen is available. During drought conditions, plants may sacrifice some nodules to conserve water, demonstrating the dynamic nature of this biological contract. As climate patterns shift, understanding these adaptive responses becomes increasingly crucial for maintaining productive agricultural systems.

Extension specialists emphasize that observing nodule color provides critical diagnostic information. White or green nodules indicate inactive rhizobia, while the desired pink or red color shows active nitrogen fixation. Brown nodules signal senescence. These visual cues help farmers make timely decisions about supplemental fertilization when the symbiotic system underperforms.

The ecological ramifications extend far beyond individual fields. Properly nodulated soybean crops leave residual nitrogen that benefits subsequent crops in rotation. This biological nitrogen fixation reduces nitrate leaching compared to synthetic fertilizers, protecting water quality. Researchers estimate that soybean-rhizobia symbiosis globally fixes nearly 5 million metric tons of nitrogen annually - equivalent to billions of dollars in fertilizer value.

Field trials consistently demonstrate that inoculation with appropriate rhizobium strains can increase yields by 8-15% compared to uninoculated fields relying on native soil rhizobia. However, the quality of inoculants varies significantly, prompting careful farmers to monitor expiration dates and storage conditions. Some operations now use liquid inoculants applied directly in the seed furrow for more reliable results than traditional seed-applied peat formulations.

As agricultural systems strive for greater sustainability, the soybean-rhizobia partnership offers a blueprint for productive biological solutions. Ongoing research into signaling pathways and genetic compatibility may lead to even more efficient symbiotic pairs. For now, careful field observation remains the farmer's most valuable tool for nurturing this remarkable natural nitrogen factory beneath our feet.

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025