The growing popularity of artificial sweeteners as sugar substitutes has sparked intense scientific debate about their long-term effects on human health. While these zero-calorie additives help millions reduce sugar intake, emerging research reveals a complex relationship between non-nutritive sweeteners and our gut microbiome that extends far beyond their intended purpose. This deep dive explores what cutting-edge studies tell us about how sugar alternatives may be quietly reshaping our microbial ecosystems with consequences we're only beginning to understand.

The Gut Microbiome: An Unseen Metabolic Organ

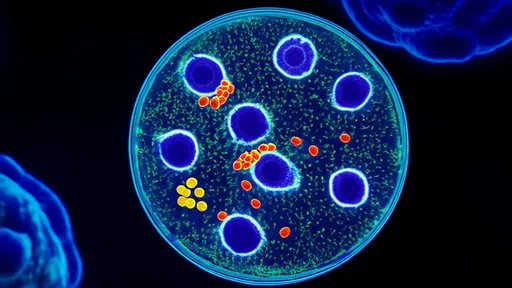

Our intestines harbor trillions of microorganisms that collectively weigh more than the human brain. This vibrant microbial community doesn't just aid digestion—it actively regulates metabolism, immune function, and even neurological processes. The composition of these gut bacteria varies dramatically between individuals based on diet, environment, and lifestyle factors. What makes this ecosystem particularly fascinating is its sensitivity to dietary components that escape human digestion but become premium nutrition for specific microbial strains.

Artificial sweeteners present a unique case because they bypass upper gastrointestinal absorption intact, arriving unchanged in the colon where they encounter dense microbial populations. Unlike natural sugars that get absorbed in the small intestine, these synthetic compounds essentially become "microbial food" by default. Studies using advanced genomic sequencing show that even occasional consumption can begin reshaping bacterial profiles within days, though the long-term implications of these shifts remain hotly contested in nutritional science circles.

Sweetener-Specific Microbial Shifts

Not all sugar substitutes affect gut flora equally. Saccharin, one of the oldest artificial sweeteners, consistently appears in research as a potent modifier of microbial composition. Human trials involving regular saccharin consumption demonstrate increased abundance of Bacteroides genus bacteria while suppressing Lactobacillus reuteri—a strain associated with glucose regulation. This particular shift correlates with poorer glucose tolerance in otherwise healthy individuals, suggesting the sweetener might paradoxically encourage metabolic dysfunction through microbial mediation.

Sucralose tells a different story. While initially considered biologically inert, prolonged exposure appears to reduce overall microbial diversity—a hallmark of gut dysbiosis. Of particular concern is sucralose's apparent inhibition of beneficial bifidobacteria coupled with increased activity of bacterial enzymes involved in breaking down mucin, the protective lining of the intestinal wall. This dual effect raises theoretical concerns about long-term gut barrier integrity, though human data remains limited beyond two years of continuous use.

Stevia and sugar alcohols like erythritol present a middle ground. These plant-derived alternatives show milder microbial impacts in short-term studies, though their fermentation by certain gut bacteria can produce noticeable changes in gas production and bowel movement patterns. The fermentation byproducts may actually benefit some microbial strains while inhibiting others, creating complex ecological dynamics that vary significantly between individuals based on their baseline microbiome.

The Glucose Tolerance Conundrum

Perhaps the most startling revelation in sweetener research came from longitudinal studies tracking artificial sweetener consumers. Multiple research groups have independently observed that regular users of certain non-nutritive sweeteners develop poorer glycemic control over time compared to sugar consumers—the opposite effect one would expect from reducing sugar intake. This paradox appears rooted in microbial changes that alter how the body processes glucose.

The mechanism involves gut bacteria adapting to artificial sweeteners by enhancing their capacity to extract energy from complex carbohydrates. As these microbial populations expand, they break down dietary fiber and other compounds into simple sugars and short-chain fatty acids more efficiently. This microbial "overprocessing" floods the host system with additional energy substrates, potentially contributing to insulin resistance despite reduced calorie consumption from sweet foods.

Generational Microbial Memories

Animal studies raise even more profound questions about the lasting legacy of artificial sweeteners. Research involving mice fed sucralose over multiple generations found microbial changes became progressively more pronounced in offspring, even when the younger generations consumed no sweeteners themselves. These inherited microbiome alterations correlated with stronger glucose intolerance in each successive generation, suggesting some sweetener-induced microbial shifts might persist long after cessation of use.

While human data spanning generations obviously doesn't exist, the animal findings hint at possible transgenerational effects worth investigating. They also underscore how profoundly our dietary choices today might influence microbial ecosystems—and by extension metabolic health—in ways that extend far beyond individual lifespans.

Personalized Responses and the Future of Sweetener Science

What makes sweetener-microbiome research particularly challenging is the highly individualized nature of microbial responses. Identical sweetener regimens produce dramatically different effects depending on a person's baseline gut flora, which varies based on geography, diet history, antibiotic exposure, and countless other factors. This variability explains why some people thrive on artificial sweeteners while others experience digestive distress or metabolic changes.

Emerging technologies like rapid microbiome sequencing and machine learning may soon enable personalized sweetener recommendations based on an individual's microbial profile. Several biotech startups are already developing at-home test kits that claim to predict how a person's gut bacteria will respond to specific sugar alternatives. While these services remain unvalidated by long-term studies, they represent growing recognition that "one size fits all" approaches to sugar substitution ignore fundamental biological variability.

Navigating the Sweetener Landscape

For consumers seeking to minimize microbial disruption while reducing sugar intake, experts increasingly recommend a rotational approach—alternating between different types of sweeteners to prevent any single compound from dominating microbial selection pressures. Combining occasional artificial sweetener use with robust prebiotic fiber intake may also help maintain microbial diversity that appears protective against some of the observed negative effects.

The scientific community agrees that more longitudinal human studies are urgently needed, particularly research tracking sweetener consumers over decades rather than months. What's already clear is that our understanding of artificial sweeteners must evolve beyond their chemical structure and calorie content to encompass their nuanced, individualized dialogues with the microbial worlds within us.

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025